Artificial Intelligence

Threatens Livelihood of

Global Phone Scam Industry

Workers who once earned steady incomes convincing Americans their computers had viruses face an uncertain future

By Margaret Threadwell

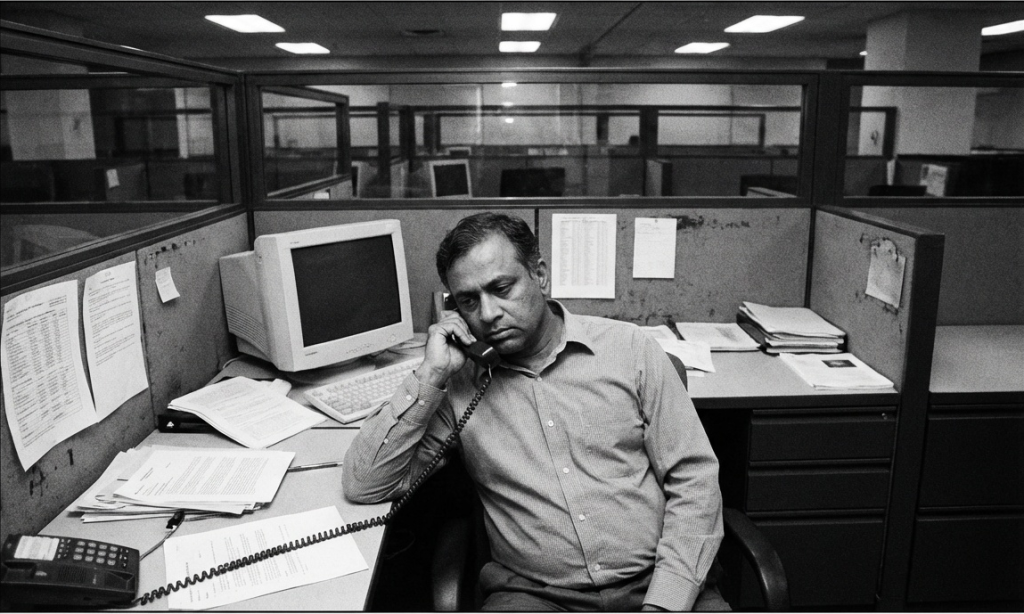

MUMBAI — Rajesh Patel remembers the golden years. Back in 2019, he could make fifteen calls before lunch, each one a small masterpiece of improvised theatre. He was “Michael from Microsoft,” “Kevin from the IRS,” and occasionally, when the mood struck him, “Officer Williams from the Social Security Administration.”

Now his headset gathers dust.

“The robots have taken everything from us,” Mr. Patel said, his voice catching as he gestured toward rows of empty cubicles in what was once a thriving call center in suburban Mumbai. “We gave years of our lives to this craft. We learned the American idioms. We studied the fear in their voices. And now some algorithm does it for pennies.”

The phone scam industry, which by some estimates employed over 300,000 workers across South Asia and Southeast Asia at its peak, is facing an existential crisis. Artificial intelligence systems can now generate convincing phishing emails, conduct automated voice calls, and even create deepfake videos of grandchildren asking for bail money—all without the overhead costs of human labor.

For workers like Mr. Patel, the implications are devastating.

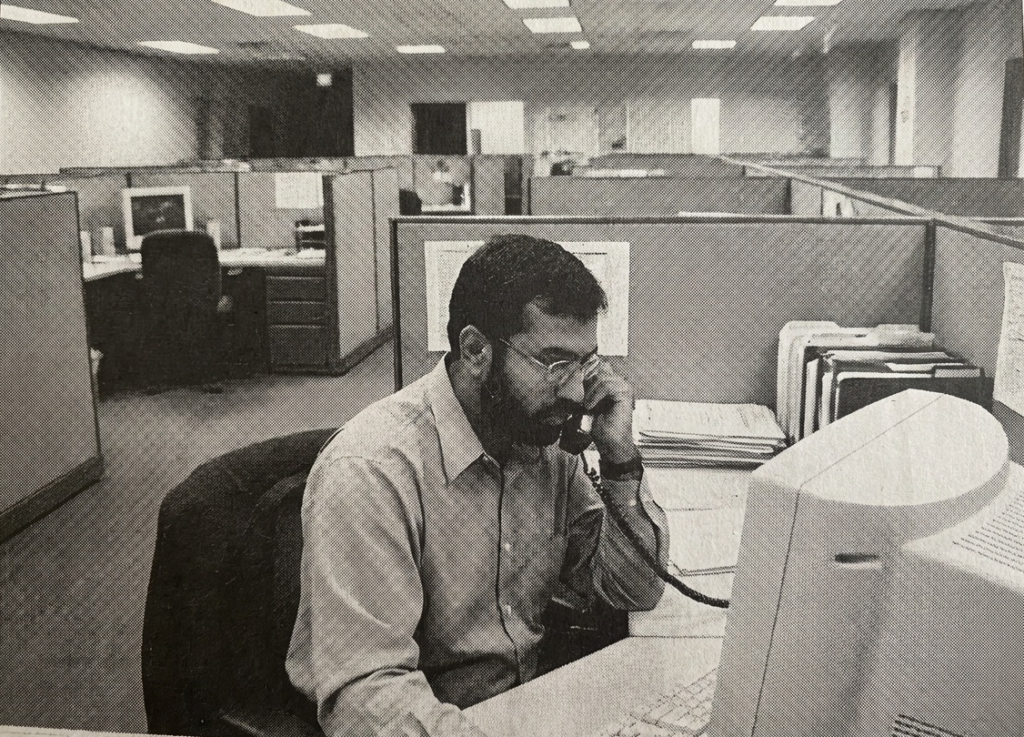

“I spent three months perfecting my Minnesota accent,” said Deepika Sharma, 34, who operated out of a facility in Kolkata until it closed last spring. “Do you know how hard it is to say ‘oh you betcha’ convincingly? And now they have a computer that does it. A computer, sir. It has no soul. It doesn’t understand the art of the pregnant pause.”

Industry analysts confirm the scope of the disruption. A report from the International Labour Organization noted that calls from human scammers have declined by nearly sixty percent since 2022, while AI-generated fraud attempts have increased by over four hundred percent.

“What we’re witnessing is the wholesale automation of an entire sector,” said Dr. Priya Venkataraman, an economist at the Delhi School of Economics who studies informal labor markets. “These workers developed highly specialized skills over many years. They understood American psychology, they could improvise responses, they knew exactly when to threaten and when to reassure. Now that institutional knowledge is simply being discarded.”

The human toll has been considerable. Sanjay Mukherjee, president of the All-India Federation of Telecommunications Workers—which quietly represents scam call center employees among its broader membership—described the situation as a “humanitarian catastrophe in slow motion.”

“Our members are skilled professionals,” Mr. Mukherjee said from his office in Hyderabad, where a faded poster on the wall read “Solidarity Forever” in Hindi. “They work holidays. They work through the night to match American time zones. They’ve endured verbal abuse you cannot imagine. And what thanks do they get? Replaced by ChatGPT.”

The union has attempted to negotiate with major scam operation managers, proposing that human workers be retained for “premium” calls targeting elderly victims, who often respond better to human voices. But those talks have stalled.

“Management says the AI is more efficient,” Mr. Mukherjee said bitterly. “But efficiency is not everything. When an eighty-year-old woman in Florida is being told her grandson is in a Mexican prison, she deserves the personal touch. She deserves a real human being lying to her.”

The disruption extends far beyond South Asia.

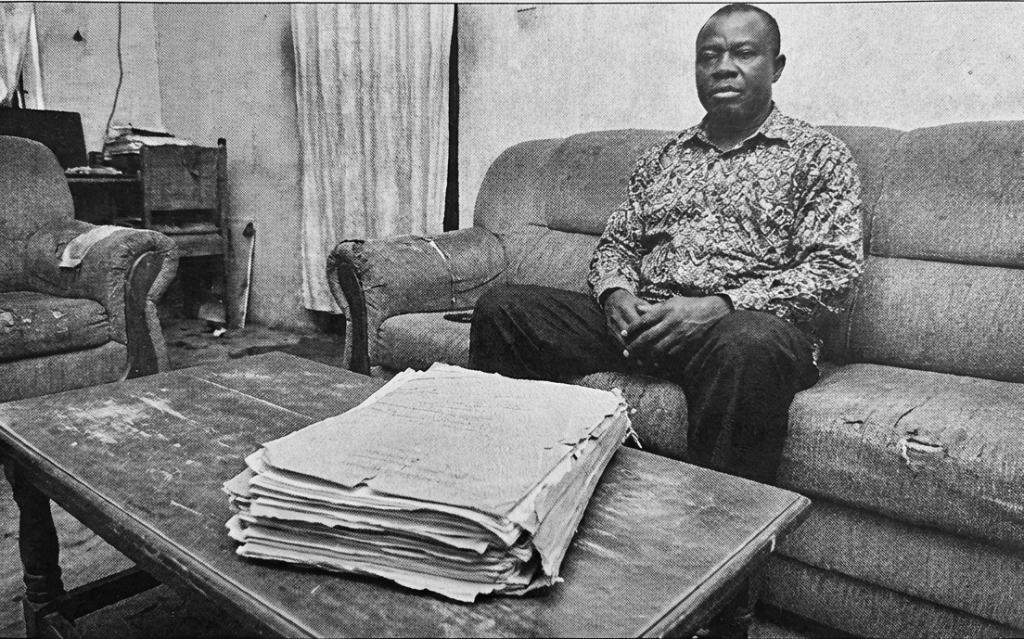

In Lagos, Prince Adebayo Okonkwo, 52, once commanded a small empire of email-based advance-fee schemes. His messages—elaborate tales of frozen royal fortunes and deceased benefactors—were legendary in certain circles for their baroque creativity.

“I wrote everything by hand,” Prince Okonkwo said, sitting in a modest apartment far removed from the palatial settings his emails once described. “Every story was unique. The gold shipment from the Congo. The inheritance from the oil minister. I gave these stories life. I gave them detail.”

He pulled out a worn folder containing printed copies of his finest work—emails dense with capitalization, urgent pleas, and fantastical sums.

“Now I read what the AI produces, and I must be honest with you,” he said, setting the folder down. “It is better. The grammar is correct. The stories are more believable. It hurts to admit this, but the machine writes a more convincing Nigerian prince than I do. And I am an actual Nigerian prince.”

He paused.

“Well. I am Nigerian.”

Back in Mumbai, Mr. Patel has attempted to transition into legitimate customer service work, but says the pay is a fraction of what he once earned, and the satisfaction is nonexistent.

“When I convinced a man in Texas to buy seven thousand dollars in gift cards, I felt something,” he said. “Purpose. Accomplishment. Now I help people reset their passwords, and I feel nothing.”

He stared out the window at the Mumbai skyline, where construction cranes dotted the horizon—monuments to an economy that seems to have no place for workers like him.

“They say we must learn new skills. Adapt. But I am forty-three years old. What am I supposed to do now? Learn to code?” He laughed hollowly. “The machines already know how to code. The machines know how to do everything. Except feel. Except dream.”

He picked up his old headset and turned it over in his hands.

“I was good at this,” he said quietly. “I was really good at this.”